English version

On April 10th, 2025, our students took part in a lecture by Professor Nataliia Romanyshyn entitled “Ukrainian Language and Identity under Soviet Totalitarianism,” held as part of the “BEYOND LANGUAGE” series. The session offered a multidisciplinary perspective on the ways language was used as a tool for ideological control and identity reshaping.

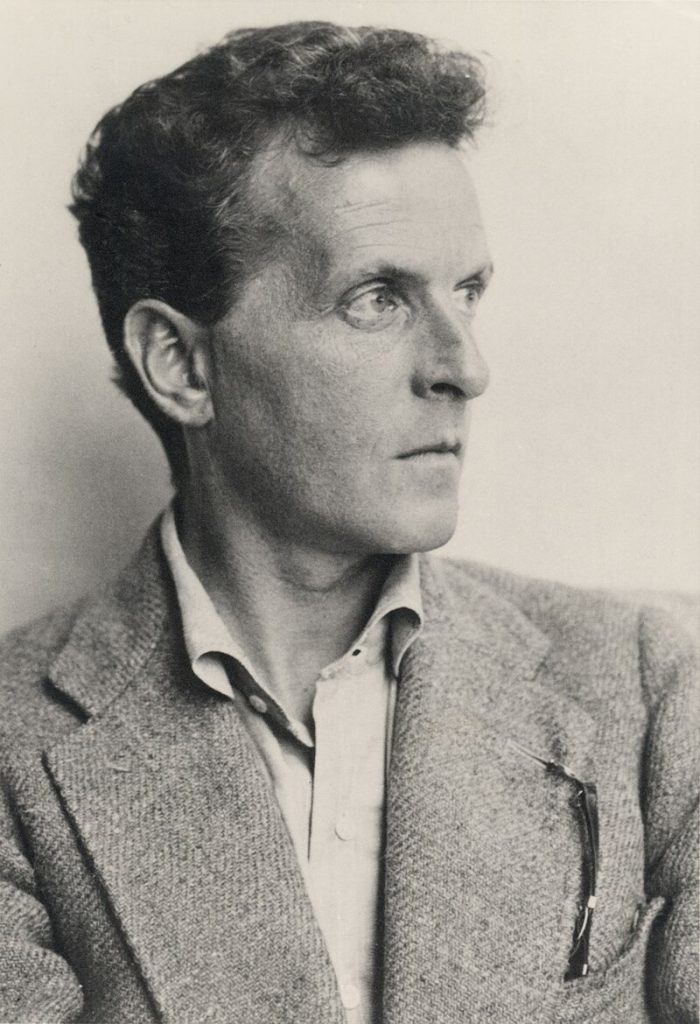

The lecture began with an exploration of the meaning and function of language not only as a tool for communication, but also as a framework through which people perceive and interpret the world. As Ludwig Wittgenstein aptly observed, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world,”[1] a statement that set the tone for a broader reflection.

Versión en español

El 10 de abril de 2025, nuestros estudiantes participaron en una ponencia presentada por la profesora Nataliia Romanyshyn, titulada “La lengua ucraniana y la identidad bajo el totalitarismo soviético”, organizada como parte del ciclo de conferencias “BEYOND LANGUAGE”. La sesión ofreció una mirada multidisciplinaria sobre cómo el idioma fue utilizado como herramienta de control ideológico y de transformación de la identidad.

La conferencia empezó reflexionando sobre el significado y la función de la lengua, no solo como medio de comunicación, sino también como marco a través del cual las personas perciben e interpretan el mundo. Como bien dijo Ludwig Wittgenstein: “Los límites de mi lenguaje son los límites de mi mundo”[1], una idea que sirvió como punto de partida para una reflexión más amplia.

The historical part of the lecture included a look at the evolution of writing systems, such as the consonantal principle of the Phoenician alphabet (an approach still visible in Arabic and Hebrew). Professor Romanyshyn also referred to the 1928 alphabet reform in Turkey as an example of how changes in writing can reflect sociopolitical shifts.

To provide a historical context, Professor Romanyshyn presented an overview of the origins and development of the Ukrainian language. There are three main hypotheses. The first one suggests that Ukrainian, Belarusian, and Russian emerged from the disintegration of Old East Slavic (the common language of the Eastern Slavs). Another theory argues that these languages developed directly from Proto-Slavic, without an intermediate Old East Slavic stage.

La parte histórica de la conferencia incluyó un análisis de la evolución de los sistemas de escritura, como el principio consonántico del alfabeto fenicio (que todavía se puede observar en lenguas como el árabe o el hebreo). La profesora Romanyshyn también mencionó la reforma del alfabeto en Turquía en 1928 como ejemplo de cómo los cambios en la escritura pueden reflejar transformaciones sociopolíticas.

Para dar contexto histórico, la profesora presentó un resumen sobre los orígenes y la evolución de la lengua ucraniana. Existen tres principales hipótesis: la primera sostiene que el ucraniano, el bielorruso y el ruso surgieron tras la desintegración del antiguo eslavo oriental (la lengua común de los eslavos orientales). Otra teoría afirma que estas lenguas evolucionaron directamente del idioma protoeslavo, sin pasar por una etapa intermedia.

A third, less widespread view, proposes an even earlier divergence of Ukrainian from the Slavic linguistic continuum. However, the final formation of the Ukrainian language as a distinct literary and cultural standard is generally dated to the 16th century. Its development varied slightly depending on the region, with western, central, and eastern dialects, each contributing to its evolution[2].

Una tercera, menos aceptada, propone una separación aún más temprana del ucraniano respecto al continuum lingüístico eslavo. Sin embargo, el proceso de formación final de la lengua ucraniana como estándar literario y cultural propio se suele situar en el siglo XVI, aunque su evolución varió ligeramente según la región (occidental, central y oriental).[2]

Building on this linguistic foundation, the focus then shifted to the case of the Ukrainian language under Soviet rule. Ukrainian was frequently labeled as a “dialect,” denied institutional presence, and excluded from domains of prestige. This deliberate marginalization was presented not only as a linguistic decision, but as a tool for erasing national consciousness.

The lecture left a lasting impression, highlighting the responsibility we all share in protecting linguistic diversity and understanding the historical forces that continue to shape the way we speak, think, and identify ourselves.

Basándose en estos fundamentos lingüísticos, la conferencia se centró en la situación de la lengua ucraniana bajo el régimen soviético. El ucraniano fue con frecuencia calificado como un “dialecto”, se le negó presencia institucional y se le excluyó de los espacios de prestigio. Esta marginación deliberada fue presentada no solo como una cuestión lingüística, sino también como una estrategia para borrar la conciencia nacional.

La conferencia dejó una profunda impresión, recordándonos la responsabilidad que todos tenemos de proteger la diversidad lingüística y de comprender las fuerzas históricas que siguen influyendo en la manera en que hablamos, pensamos e identificamos quiénes somos.

[1] Wittgenstein, Ludwig ([1921] 1922) Tractatus logico-philosophicus. Translated into English by F. P. Ramsey and C. K. Ogden. Edited by C. K. Ogden. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.

[2] Fałowski, Adam (2014) “Język ukraiński.” [In:] Agnieszka Korycińska-Huras (ed.) Procesy i procedury zarządzania na Uniwersytecie Jagiellońskim. Biblioteka Jagiellońska; 221–272.

Tekst: Kornelia Lisiewicz KMSI

Zamieszczone przez: Tomasz Górski